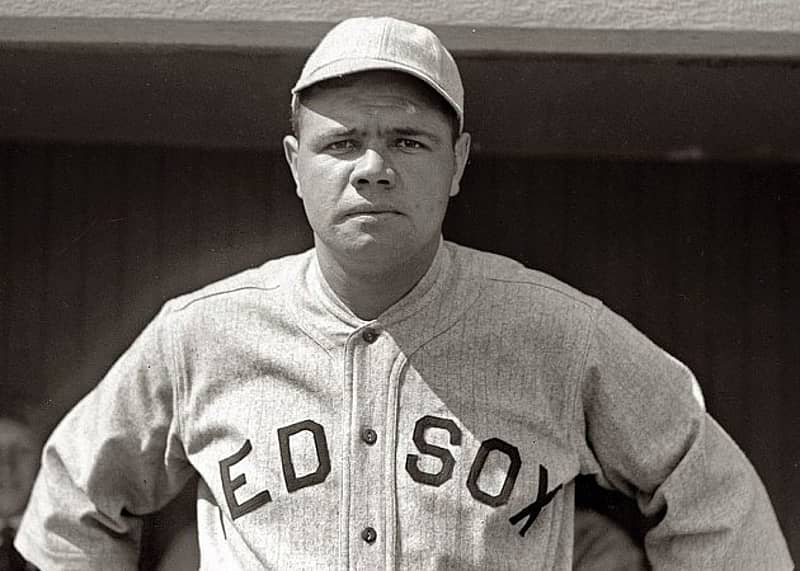

One Hundred and Eight Years Ago Today, The Babe Joins The Red Sox.

“Babe Ruth joined us in the middle of 1914, a 19-year-old kid. He was a left-handed pitcher then, and a good one. He never had been anywhere, didn’t know anything about manners or how to behave among people-just a big overgrown pea. You know, I saw it all happen, from beginning to end. But sometimes I still can’t believe what I saw: this 19-year-old kid, crude, poorly educated, only lightly brushed by the social veneer we call civilization, gradually transformed into the idol of American youth and a symbol of baseball the world over-a man loved by more people and with an intensity of feeling that perhaps has never been seen before or since. I saw a man transformed from a human being into something pretty close to a god. If somebody had predicted that back on the Red Sox in 1914 he would have thrown into a lunatic asylum.” Harry Hooper in an interview with Lawrence Ritter for “The Glory of Their Times”

When Babe Ruth stepped off the train at Back Bay Station at 10:00 AM on the morning of Saturday, July 11, 1914, he’d arrived in the capital of baseball.

Ground zero.

Not only were the Miracle Braves about to start their stunning pennant chase but the Red Sox were the game’s most celebrated team with stars such as Tris Speaker, Harry Hooper, Duffy Lewis, and Smoky Joe Wood.

Their nickname was “Speedboys” and heaven help anyone who snickered at the sobriquet in the presence of their often inebriated fan clan known as the Royal Rooters. Not only did this team win in as regular and consistent a manner as the Celtic teams of the sixties but they also possessed the sass and swagger of the Orr/Esposito era Boston Bruins. In short, the Speedboys owned both Boston and all of baseball.

Ruth arrived in the ideal city and the perfect team for his major league apprenticeship. He was fortunate to be managed by player/manager Bill Carrigan also known for his well-earned nickname of “Rough.” Carrigan not only started his newly acquired pitcher against the Indians on his first day in Boston, but he would room with him and teach him the fundamentals of the game from the ground up. In many ways, Ruth found a surrogate father in Carrigan when he arrived in Boston. Commenting on his victorious major league debut Boston Globe sportswriter Tim Murnane wrote: “All eyes were turned on Ruth, the giant left-hander, who proved a natural ballplayer and went through his act like a veteran of many wars. he has a natural delivery, fine control, and a curve ball that bothers the batters, but has room for improvement, and will undoubtedly, become a fine pitcher under the care of Manager Carrigan. He held the Naps to five hits in six innings, with one strikeout, but was hit hard in the seventh, when the visitors tied the score by scoring two earned runs on singles by Kirke and Chapman and a sacrifice and single by O’Neil. That was the curtain for the Oriole importation, and he looked weak only in comparison with Dutch Leonard, who pitched the last two innings, putting six men out in order, four of them on strikes.”

Only two seasons before Ruth’s arrival the Red Sox had christened Fenway Park in 1912 with a record-setting world championship season. Fans were hungry to see a repeat performance and did with the unexpected Fenway Park appearance by the Boston Braves for the last two months of the regular season and victorious World Series over the heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics.

Accompanying Ruth to Boston following his purchase from the minor league Baltimore Orioles was fellow pitcher Ernie Shore. Before long Shore joined a pitching staff featuring Ruth, Dutch Leonard, Carl Mays, Rube Foster, and in 1915 Joe Wood.

As the greenest of the young pitchers, Ruth became a project for Carrigan. The wily catcher picked up on many of Ruth’s bad habits such as allowing his tongue to hang out when he threw his curve. Such a trait would have proved disastrous to the rookie if allowed to persist. Carrigan also paid his protégé’s salary daily after having learned of his wild partying and womanizing.

In 5 1/2 seasons with the Red Sox Ruth became nothing less than the best left-hander in the American League winning 89 games with 46 losses and achieving a perfect 3-0 record in World Series play, His series record for consecutive scoreless innings would last for over half a century before being broken by Yankee Hall of Famer Whitey Ford in the sixties. In his final season with the Red Sox, he alternated between pitching and playing outfield and socked a single-season record-shattering total of 29 home runs. The best lefty in the league had suddenly become the best player and hottest property in the majors.

His sale to the Yankees for one hundred thousand dollars and a mortgage on Fenway Park announced to the world in January 1920 is still considered one of the dark days in Boston sports. However in 15 seasons with the Bronx Bombers Ruth was a member of four world championship teams, a far lesser ratio of titles to seasons than his stint in Boston highlighted by three world titles in 5 1/2 seasons. Ruth continued to make his off-season home in Sudbury for years and remained an active board member of South Boston’s Pere Marquette AC during that time as well. In 1935 he returned to Boston as a member of the Braves for the last 28 games of his career which included a golden afternoon at Forbes Field where he hit the last three of his 714 home runs.

So, today on the 108th anniversary of his arrival in Boston let us celebrate the Blessing of the Bambino and the curse of not being able to avail ourselves of time travel to see the promising start of baseball’s greatest career.