”I loved to run as a kid. I’d see a green field and I’d feel so much joy at its beauty that I’d just have to tear across it at top speed. Everyone else stopped running after high school, but I never stopped.”

“I am now twenty-one years old, and I’ve been running in the woods like this for the last ten years alone, solitary, secretly. I’m rediscovering something here that has been all but lost in modern society. I’m reconnecting with ancient roots, to a time when women were goddesses and ran through the woods with their hunting dogs, a time when the wonders of the earth were new and their causes mysterious. I’m recovering from a thousand years of civilization and reconnecting with an ancient human potential, some primal unity of mind, body and spirit, lost in modern society.”

-Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb, c. 1963

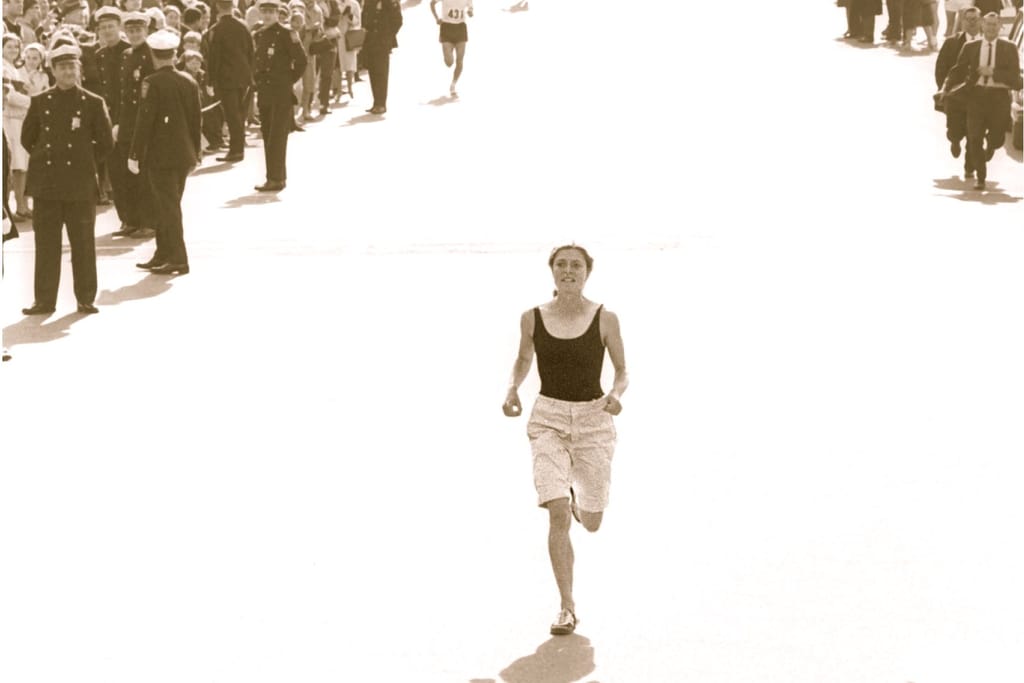

Running pioneer Roberta Gibb, the first woman to run the Boston Marathon, is a charming combination of wisdom, intellect, grit and an endearing and enduring grace.

Her historic run to Boston in 1966 came at the conclusion of a series of unlikely circumstances that would and should have prevented her historic journey.

Let me recount the details of this most improbable triumph.

In the fall of 1965, Winchester native Gibb, newly married, living in San Diego, and running recreationally for up to 40 miles at a stretch, wrote to the Boston Athletic Association, requesting an official entry to the 1966 Boston Marathon.

Their rejection letter, which soon followed, was both jarring and inspirational.

Dear Mrs. Burgay,

We have received your request for an application for the Boston Marathon and regret that we will not be able to send you an application.

Women are not physiologically capable of running a marathon and we would not want to take on the medical liability. Furthermore, the Boston Marathon is a men’s division event. The rules of International Sports and the Amateur Athletic Union, do not allow women to run races more than the sanctioned one and a half miles.

Sorry, we could not be of more help.

Sincerely,

Will Cloney

The BAA’s letter merely added fuel to a competitive fire that had already been burning for quite some time. It arrived in the midst of an era where many previously accepted societal norms related to topics such as race, gender and roles were being challenged. And Gibb, in her own quiet, persistent manner, channeled the rage she experienced at her rejection in a singular mission to overcome their premise. All of which occurred while overcoming a series of circumstances containing elements of screwball comedy and inspirational drama.

First off, though Gibb had already been running for a dozen years, she did so without the benefit of coaching.

In her memoir, “Wind in the Fire,” she recounted her training for her first Boston Marathon: “I have no idea how to train, no running clothes, no running shoes. I run in nurses’ shoes and a black tank top bathing suit over which I pull some shorts and a cotton shirt.”

“Yesterday I was just running for the sake of running, and for the peace it brings and the time it allows for thinking. Today, I have a purpose, a goal. It is the first time in my life that I’ve decided on my own on a long-term goal-something that I want to accomplish for myself-something that I will work on bit by bit until I accomplish.”

Her journey to the starting line itself, apart from years of training, is as remarkable, and in many ways, more remarkable, than her historic run.

Following a disagreement with her husband as to whether she should trek to Boston to run the race, she grabbed their motor scooter and raced to the San Diego bus station with barely enough money to purchase her tickets for the 3000+ mile journey. On the way she’d purchased a pair of boy’s running shoes as the nurse’s shoes in which she’d trained were simply too heavy in which to run a race.

Three days later, she arrived at Boston’s Park Square depot and later wrote, “Stiffly I pry myself out of my seat and disembark. It is April 18th and one day before the marathon, and I can barely walk. Outside it is cold, gray, and desolate.”

That night, she consumed a huge meal more suited to a football lineman than a that of pre-race fare for a first-time marathoner. And before she could even begin digesting the roast beef, potatoes, and apple pie, her father sternly forbade her from leaving the house while expressing his opinion that she was delusional in a quest he feared might result in her death.

The following morning a tense breakfast was marked by her father’s declaration that she not run the race, which was followed by her equally emphatic reply that she’d run, even if it meant taking a taxi from their home in Winchester to Hopkinton. She’d simply worked too hard and endured too arduous a bus trip to be denied.

Fortunately, her mother relented to her plaintive appeals and simply asked Bobbi to serve as navigator as she drove her to the starting line in Hopkinton.

The Boston Marathon, then in its 68th year, was a race of barely twelve hundred official runners supplemented by a handful of so-called bandits, namely runners who joined the back of the field from the bushes and ran without the benefit of an official number.

It was within their number that Gibb would make history.

Within five miles of the start, her fear of possibly being forced from the race by angry male runners vanished as many offered their vocal support. In a pack that included a runner name Alton Chamberlain, the men agreed the road was free and responded in unison that they would not allow anyone to throw her out.

At the halfway mark of Wellesley College she was greeted with cheers of “Great Great! Keep on running! A woman! God, a woman! A woman is running! Do it girl! Go! Go! Go! Go!

As she ascended the first of the Newton hills, she learned she was running at a sub-three-hour pace.

However, the final miles, from Boston College to the Prudential Center finish became a virtual gauntlet of broken blisters, aching quads, dehydration, and her battle to reject the temptation to simply quit.

As she slowed to a jog, several buses containing men who’d already dropped out shouted cheers of encouragement as she made her way to the final stretch of the famed course.

She’d later write, “I turn left, on to Boylston Street. Suddenly the road opens up. Thousands of people line the streets. Bleachers are packed. A roar goes up. The press truck rolls along beside me, flash bulbs, the announcer, and police. I pick up my pace and trot across the finish line in a time of three hours and twenty minutes I’m told, ahead of two thirds of the pack. Not bad. Alton comes to welcome me. Some kind soul throws a wool blanket over my shoulders. I reach up and shake the hand of a nice looking square-built man in a dark blue wool coat. He is the Governor of Massachusetts, John Volpe, who has come down to congratulate me.

The next day’s Boston Record-American featured her photo on the front page accompanied by the headline, “Hub Bride First Gal to Run Marathon.”

She returned to run Boston in 1967 and 1968 where she also finished first in the unsanctioned field.

In 1972, the AAU finally changed their rules and the first official women’s field was accepted.

Gibb remarried, earned an undergraduate degree in both mathematics and philosophy and added a law degree while also working on epistemology and color vision at MIT.

She is also a critically acclaimed sculptor and author, and was named to the Road Runners of America Hall of Fame in 1982.

In June of 2011, The Sports Museum honored her with the running legacy award at their annual Tradition ceremony.