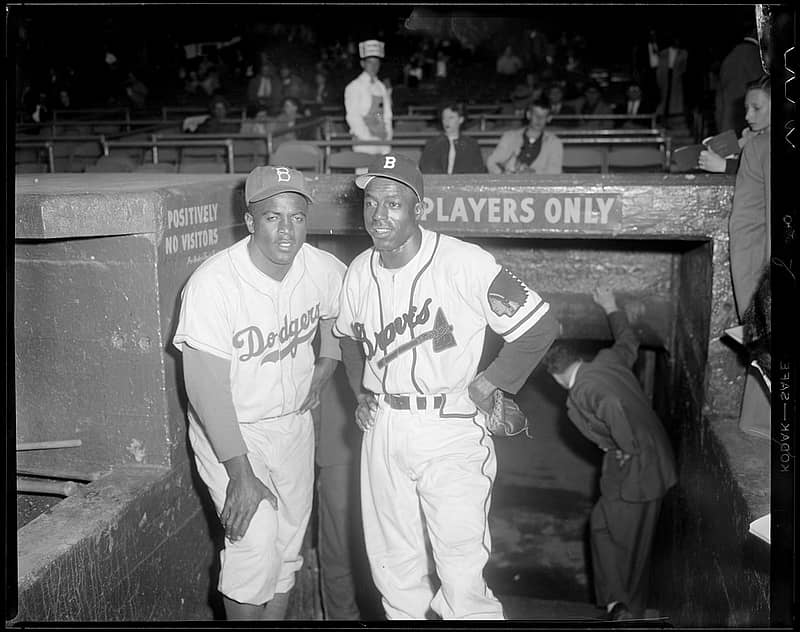

The Jet, Boston Braves Center Fielder Sam Jethroe

“Center fielder Sam Jethroe was both a fan favorite in Boston and led a group of African-American and former Negro League players that would deliver the franchise’s second world championship in Milwaukee. Their number included Buzz Clarkson, George Crowe, Billy Bruton, Wes Covington, Felix Mantilla, and a young shortstop named Henry Aaron.”

-George Altison, Founder, Boston Braves Historical Society

“I was a Braves fan and Sam was my hero in the team’s last days in Boston. I was often part of what seemed like crowds of only 700-800 fans at Braves Field where, on one occasion, I got him to look up and smile at me after I’d yelled “Mr. Jethroe!.” This was back in the days when the National League showcased the talents of men like Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, and Roy Campanella making it the progressive sporting equivalent of the Democratic Party.”

-Christopher Lydon, NPR radio host and New York Times and Boston Globe journalist

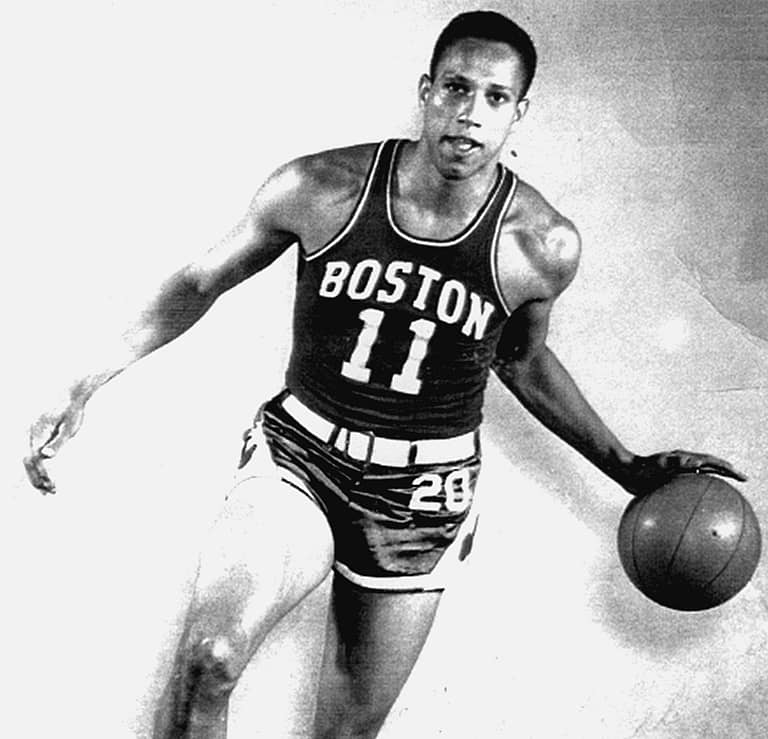

Viewed through the lens of historical perspective, the date of April 21, 1950, should stand as a significant marker in Boston sports history, as that was the day that 7,308 fans welcomed Boston Braves center fielder Sam Jethroe for the home opener, at which he became the first African-American to play for any of the city’s four major professional sports franchises.

Just three days earlier Jethroe, in his first-ever game, played at New York’s Polo Grounds and helped lead the Braves to an 11-4 win over the Giants.

In his Boston Globe account of the game, Jack Barry wrote: “Fans will relish the base-running antics of Sam Jethroe, whose speed and daring on the paths upsets opposing pitchers. The negro star broke into the majors by crashing a home run, getting two hits, driving in two runs, and fielding acceptably.”

In sharp contrast, news accounts from the Braves home opener reported on a 2-2 tie that was rained out in the eighth. And apart from a brief reference to his being thrown out in the third inning by future Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn while trying to stretch a single, the Globe made no mention of the historic significance of the occasion.

In fact, much of the pre-game buzz focused on the prospects of the recently acquired (via trade with the Giants for Alvin Dark and Eddie Stanky) trio of Sid Gordon, Buddy Kerr, and Willard Marshall, as well as the return of Cambridge native and Phillies first baseman Eddie Waitkus, who’d only recently recovered from the gunshots he’d suffered as the result of an encounter with a crazed fan at Chicago’s Edgewater Beach Hotel.

However, as the season progressed, Braves fans grew to love the player nicknamed “The Jet,” as he captured National League Rookie of the Year honors while batting .273, scoring 100 runs, socking 18 home runs, driving in 58 runs, and stealing a league-leading 35 bases. He also was the league leader in assists despite the fact that defense was the weakest part of his game.

What made his achievement truly remarkable was that he achieved it at the age of 33 though he’d lied to the Braves while claiming to be 28.

Such was the manner in which an eight-year Negro League veteran had to navigate the treacherous waters of organized baseball while seeking to become one of the select handful of African-Americans to reach the once unthinkable plateau of the major leagues.

In fact, according to baseball historian Bill Nowlin, Jethroe, who’d originally signed with the Brooklyn Dodger organization, was briefly considered by Branch Rickey as a possible candidate to become the first African-American to break the color line. Instead, Jackie Robinson gained that distinction, while Jethroe joined the Dodger Triple-A affiliate in Montreal in 1948 where he batted .322 in 76 games. The following season he batted .326 in 153 games while setting an International League single-season stolen base record with 89, before being sold to the Braves for an amount reported to be $100,000.00.

In today’s major leagues, Jethroe would likely be tabbed as the rare four-tool designated hitter for a salary of at least twenty million per season. In 1950, his reward from fans, gifted to him on a day in his honor at Braves Field was a TV, radio, easy chair, set of matching luggage, and an all-expenses-paid week at a hunting lodge in Rangely Maine. When the event was initially proposed he’d asked that instead of gifts, a check be made out to the Negro College Fund. His request was granted and included with the gifts he received on a day when Boston Mayor John Hynes served as master of ceremonies.

In 1951, Jethroe batted .280 while also leading the league in steals with 35. His offense remained consistent as he scored 101 runs, once again hit 18 home runs, and drove in 65 runs. However, his defense remained a problem, despite the fact that he began wearing glasses that June, he once again led the league in outfield errors for the second consecutive season.

Following a sharp drop-off in production in his third season the Braves demoted him to the minors where he played for the Toledo Mud Hens before being traded to the Pirates on December 26, 1953. He never played a single game for the Braves in Milwaukee.

Jethroe had only one final major league at bat for the Pirates while appearing in just two games. His professional career continued in the minors for another six seasons spent mostly in Toronto.

In retirement, he moved to Erie, Pennsylvania, where he operated Jethroe’s Bar and Restaurant. In the early nineties, his business failed and in 1994 he lost his home to fire.

When Boston fans learned through news accounts that Jethroe was forced to sell his Rookie of The Year award, the Boston Braves Historical Society took up a collection and sent their former hero a check for over $2,100.00. They also invited him back to Boston as a special guest for their annual luncheons in 1992 and 1995, where he was greeted with standing ovations while seated at the head table with former teammates such as Warren Spahn, Tommy Holmes, and Johnny Sain.

In 1995, he made headlines once again, as he petitioned the major leagues for pension benefits though he was nearly a full season shy of the four required. His attorney, John Puttock, argued that Jethroe and other former Negro League players with short major league careers had been deprived of the opportunity to start sooner solely based on the color of their skin.

And though the suit was dismissed in 1996, U.S. Senator Carol Mosely-Braun (D-Illinois) brought the issue to the attention of White Sox principal owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who prevailed upon fellow owners to start a fund that would grant former Negro League players annual stipends of between $7,500.00 and $10,000.00.

Jethroe later remarked, “I can’t tell you how appreciative I am of what the owners have done.”

He also reflected on his three seasons while observing, “I loved the Boston fans-they used to chant, “Go Go Go,” every time I reached base. The only confrontations I had were on the field.”

The first Boston Brave to win Rookie of the Year honors died on June 16, 2001, at the age of 84.

(Richard A. Johnson)